The management of Intellectual Property (IP) in the digital realm faces significant challenges, necessitating the development of a new IP management system in anticipation of advanced AI technologies and the emergence of various IPs utilizing these technologies.

Creators can register their IP on the Story Protocol to easily track the use of their IP and enforce rights to earnings from derivative IPs through code. This offers a structured approach to IP registration, licensing, and royalty distribution.

By protocolizing the system that protects and enhances creators' IPs, the Story Protocol will lay the groundwork for further expansion of the digital world's IP industry, ultimately becoming a liquidity layer for Programmable IP.

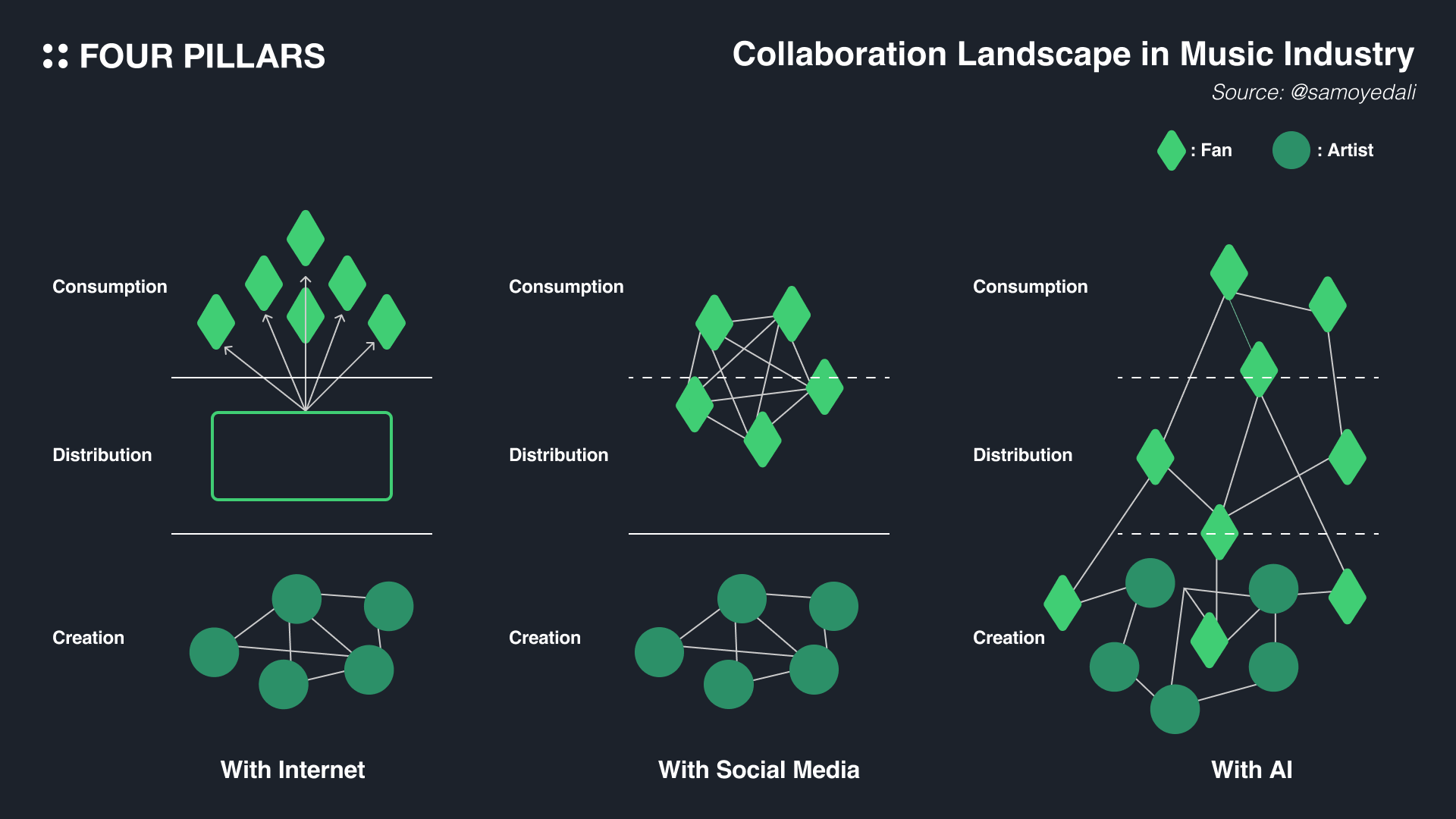

Collaboration is key in music. It takes the efforts of many people to complete a song, and it's hard to do it with just one person's ideas or efforts. Recent advances in the internet, social media, and AI technologies have dramatically changed the paradigm of music collaboration.

Source: Donda by Drake

Before the internet, artists had to be physically present in the same studio to make music together, limiting the scope of their collaboration. With the advent of the internet, however, it became possible to send each other melodies worked out on their own computers as wav files or flp project files without any physical limitations.

How many people were involved in the song "Hurricane" from Kanye West's Donda? According to this source, a total of 43 people worked on this single song, including 6 on vocals, 11 on production, 18 on engineering, and 23 on songwriting and lyrics.

While not as Kanye West's Hurricane, having multiple people on a song is already a common trend. For example, if you look at the track No Stylist by Destroy Lonely, Cxdy and Chef9thegod contributed to the song, with Chef9thegod creating the overall melody and Cxdy creating the drum line. This division of labor is partly due to the natural specialization of each composer as the industry develops, but I think the commercialization of the Internet is the biggest reason.

Source: Sabrina Carpenter @ Spotify

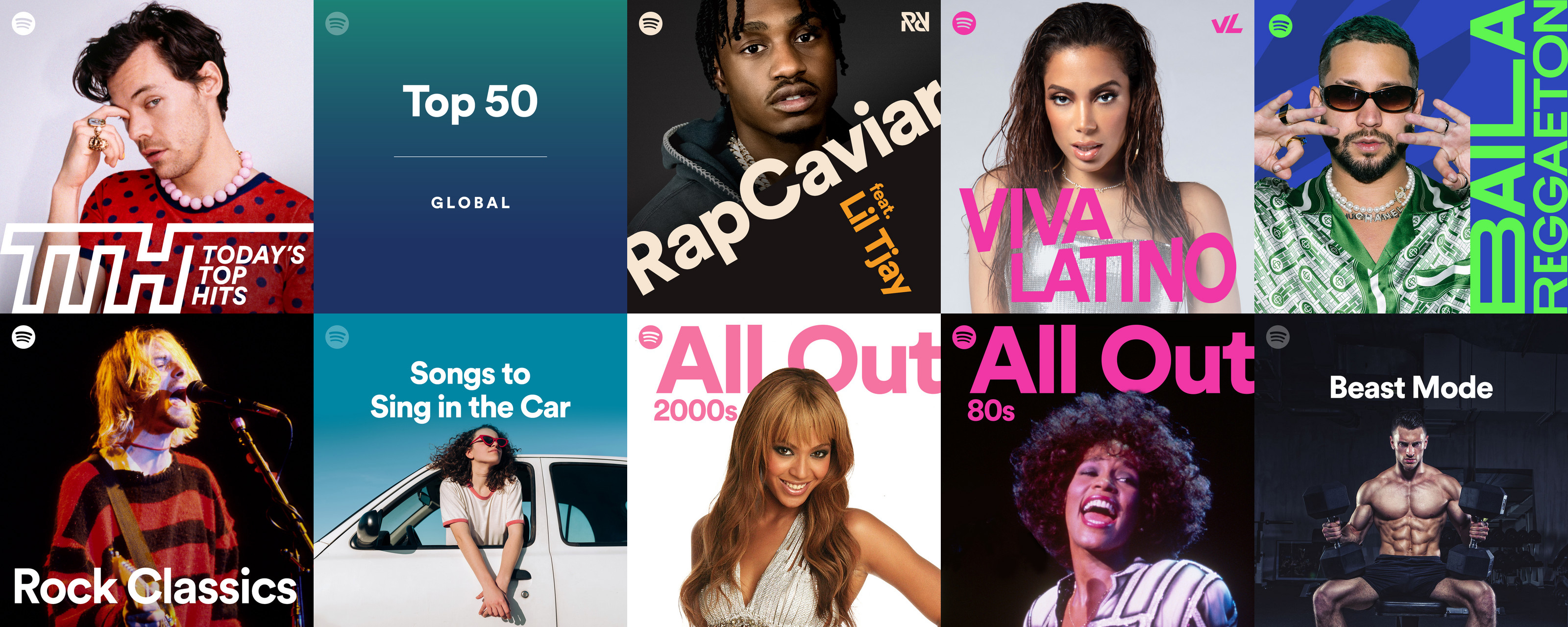

With the advancement of the internet, social media emerged, which began to significantly influence how music is distributed after its release.

Currently, the most important platform for the music industry is TikTok. Due to its short video length and nightcore trend, influencers have started to create TikToks with "Speed Up" versions of existing songs. In fact, unofficial Speed Up versions have always existed on YouTube, but the popularity of these videos on TikTok has prompted artists and labels to release Speed Up versions as official tracks.

In addition to TikTok, individuals' curated playlists on YouTube and Spotify are also playing a big role in promoting and discovering music. With so much music out there, I'm sure I'm not the only one who has had the experience of listening to a playlist curated by someone with good taste on YouTube, only to find a great song in the middle and go back to search for the artist. For example, this playlist is very popular with +12M views and +1.2K comments, despite only featuring Korean indie artists. Being included in a popular playlist on Spotify is now a crucial factor in a track's success.

Source: @jenny____ai

The track "Heart on My Sleeve" by Drake and The Weeknd was the most trending song of Q2 2023, but the problem is that it wasn't released by the two artists, but by an anonymous TikTok user named "ghostwriter977" using the AI-generated voices of both artists. Heart on My Sleeve was released to all music streaming platforms on April 4 and was taken down by UMG on April 17. In that short period of time, it garnered 600,000 streams on Spotify, 275,000 views on YouTube, and +15M views on TikTok. Over a thousand TikTok videos were created, and Billboard estimated that the song would have generated around $9400 overall. If Drake or UMG had created it themselves, it would have been a huge viral marketing move, but if they didn't, it's proof that we're at the beginning of an era where anyone can create a song with the voice of any celebrity they want, with the help of AI.

In fact, Voicify makes it easy to create your own AI cover songs, and Mubert lets you create your own mood music. Splice, the largest music sample service, now uses an AI model trained on their library to find the best combination of samples and make recommendations.

Taken together, the emergence and commercialization of technologies such as the internet, social media, and AI have made collaboration between people involved in the music supply chain easier and more active. With the advent of the Internet, collaboration between artists has increased; with the advent of SNS, collaboration between artists and their consumers has increased; and with AI, the boundaries between artists and consumers are blurring and the scope of collaboration is increasing. In particular, before AI, collaboration between artists and consumers was limited to distribution and promotion, but now it will become a regular part of music creation. For example, if Drake fans don't like his new album, they'll start to DIY songs in their own style with Drake's voice.

Collaboration is an important foundation of culture and industry, but as more and more actors participate in collaborations, the problems are noticeably increasing. This is mainly due to issues around credit.

As collaborations between producers become more frequent, it's not uncommon for lesser-known producers to not be credited. For example, Kanye West produced the beat for Nas' "Poppa Was a Playa" early on, but his mentor D-DOT didn't credit him. More recently, a German Billboard producer named PVLACE has come under fire for taking beats and samples from his former colleague Gunboi without authorization and selling them under his own name. There are two main reasons why these things happen.

Difficulty in tracking creations: beatmakers often send their samples to various producers, and it's impossible for them to keep track of whether or not their samples have been used by a producer. So, if a malicious producer uses your sample without authorization and doesn't pay you, it's hard to know. It's also unrealistic to prove that your sample was used in that track.

The complexity of the copyright process: For big-name producers, there are people and companies that take care of the legal aspects of copyright for them, but it's not easy to navigate the process as an individual. For example, if you want to get paid globally for your music, you must join multiple copyright institutes in each country, which is expensive and time-consuming, not to mention the problem of double contracts. Therefore, when it comes to collaborations, lesser-known producers are more likely to just do what the famous producer tells them to do.

Because of these difficulties, it is not easy for lesser-known producers to keep 100% of their rights when collaborating.

Source: RouteNote

In reality, top TikTok influencers and YouTube creators are paid by labels to create promotional content for specific songs. Of course, these creators are the starting point for a viral video, but the viral needs the help of other individual creators to continue. It's only through individuals who create TikTok and YouTube videos for fun, out of fandom, or for self-fulfillment that virality can be created and sustained from the bottom up.

However, these casual influencers have a hard time claiming credit for the viral impact they have on a particular track. TikTok requires a high level of followers and viewership in order to monetize the video itself, and there are limited geographies available. On YouTube, music playlist videos can't be monetized with AdSense, so it's hard to monetize them unless you partner with an external brand, which is only possible for high-profile accounts. On Spotify, in-house curators are highly compensated, but external curators have no way to make money.

All of these platforms have one thing in common: they reward a few well-known creators, but they don't reward the small, individual indie creators who are often the backbone of a viral video.

The number of cover tracks created by artists using AI-generated voices is not likely to decrease in the future. In this situation, artists and labels need to be able to assert their rights. The major labels are already in a war with AI over the use of their libraries without permission, but it's unlikely to stop this trend. Artists like Grimes have taken the opposite approach, and instead of leaving their AI-generated voices open for easy use, they've forced a 5:5 royalty revenue split for commercial use.

In reality, the changes and issues discussed so far are the same across the IP industry, not just in music. I believe that the underlying cause of these problems is the lack of an Internet-based IP management system.

In the United States, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) has been attempting to address the digital age since the 1990s. The DMCA broadly includes the following provisions:

Prohibition on circumvention of technological protection measures: Prohibits the circumvention of technological protection measures to prevent unauthorized access to and copying of digital content.

Protects Online Service Providers: Online service providers, such as YouTube, have difficulty verifying that content posted by users violates copyright. The DMCA exempts online service providers from liability for copyright infringement if they comply with certain conditions.

Notification and takedown procedures: If a copyright holder discovers copyright infringement, they can notify the online service provider and the content must be removed.

Most online platforms we know of follow this provision of the DMCA to monitor for copyright infringement. For example, YouTube's Content ID system was heavily influenced by the DMCA. This is a system that automatically checks uploaded videos against YouTube's database to see if they violate copyright, and if they do, various actions can be taken at the will of the copyright holder. If the system misses it, the platform can still remove the video under the DMCA if the copyright holder manually requests the removal.

In my opinion, the DMCA has two major problems.

First, the DMCA is outdated. While it's great that the rights of the original creator are respected, social media and AI have led to more collaboration and secondary creation, and the DMCA hasn't kept up with these changes.

Second, the DMCA does not provide copyright holders with specific guidance or methods on how to manage and track their IP, so while the DMCA is theoretically meant to protect the rights of original authors, in practice, it fails to do so. Unless they are part of a large company, copyright holders must rely on third-party services at their own expense and resources.

The DMCA served its purpose well in the early days of the Internet. But now we need a new infrastructure. I say infrastructure, not regulation, because, in my opinion, regulation only exists to prevent certain behaviors, and we are not in that era. An infrastructure for digital native IP that is appropriate for current trends should do the following:

Provide tools and guidance for original authors to track and monitor how their work is being used. Simply saying, "If your copyright is infringed, you can always take it down," doesn't take into account the realities of the situation. You need to take it a step further and provide a method or tool that makes it easy for anyone to see how their copyright is actually being used.

We need to make sure that both original and secondary creators benefit. Original authors should be able to ensure that their rights are not infringed upon, while secondary creators should be able to re-create existing IP with confidence and claim credit for it.

Source: Story Protocol

In a nutshell, Story Protocol is an infrastructure that provides an on-chain IP registry and a framework for extending those IPs. Story Protocol is intended to be a new infrastructure for digitally-based IP. It is not intended to replace the legacy regulation and infrastructure that already exists, but just as arXiv.org has become an increasingly important parallel institution for academic papers, we believe that Story Protocol can play a similar role for digitally-based IPs.

Story Protocol adopts a structure inspired by TCP/IP, aiming to become a Programmable IP Layer. It is primarily composed of a data layer, referred to as Nouns, and a functional layer, known as Verbs (Modules), on top of which lies the ecosystem utilizing the Story Protocol.

Nouns: Acting as the data layer, this includes the core elements of the Story Protocol, such as IP Assets, licenses, and royalties.

Verbs: This layer defines the various actions that can be taken with the data defined in Nouns.

Let's explore the key elements defined in Nouns within the Story Protocol.

4.2.1 IPAssets

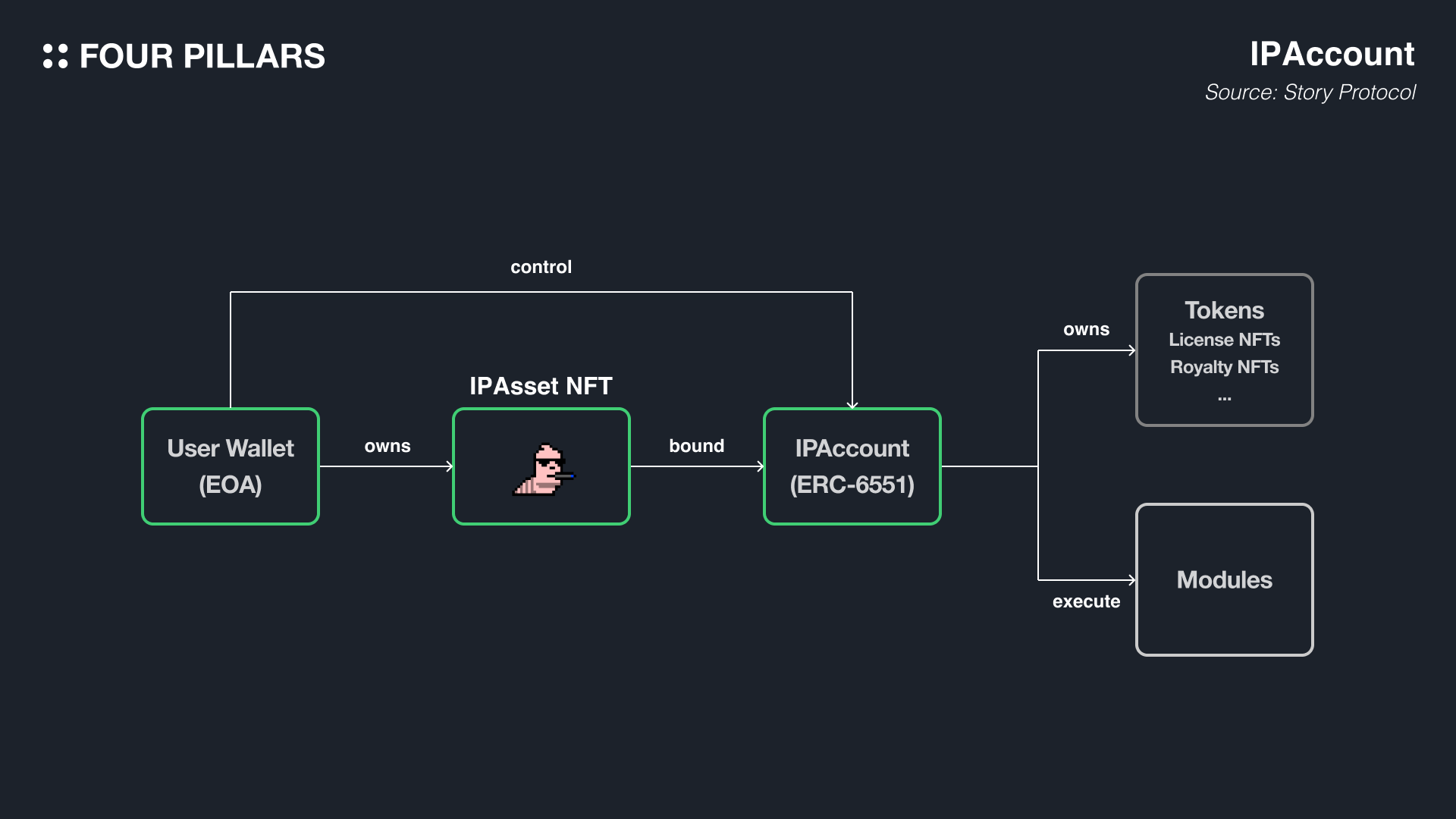

In the Story Protocol, IPs are known as IPAssets, representing on-chain NFTs that depict IPs and associated IPAccounts. Unlike static NFTs, IPAssets are inherently programmable, serving as the basic units of the Story Protocol. IPAssets encompass metadata like the type of IP, the creator, the IPA number, etc. An important attribute to note is the IPAccount, as the address of the IPAccount is included in the IPAsset as a unique ID, facilitating easy management and tracking of related information.

4.2.2 IPAccount

IPAccounts are accounts based on a modified version of ERC-6551, paired with each IPAsset, and transferred alongside the ownership of the IPAsset. Being ERC-6551 compatible, they can hold tokens like License NFTs and royalty NFTs and execute various Modules. All interactions within the Story Protocol revolve around the IPAccount, enabling key functions like licensing, royalty sharing, and remixing. The core functionality of an IPAccount is to call any Verb (Module) through the execute() function.

The primary role of a Module is to alter data/state related to IP. While Noun records data related to IP, Module (Verb) provides a framework for interacting with this data. In addition to basic Modules, the Story Protocol allows ecosystem developers to build Hooks based on the Module framework. Let's analyze the major modules:

4.3.1 Licensing Module

The Story Protocol can be seen as a social graph defining relationships between IPs on the blockchain, where licensing defines how derivative IPs can connect to the social graph. Creators within the Story Protocol can recreate various IPs into videos, images, etc. It's crucial to specify the rights of IPs in this process, managed by the Licensing Module.

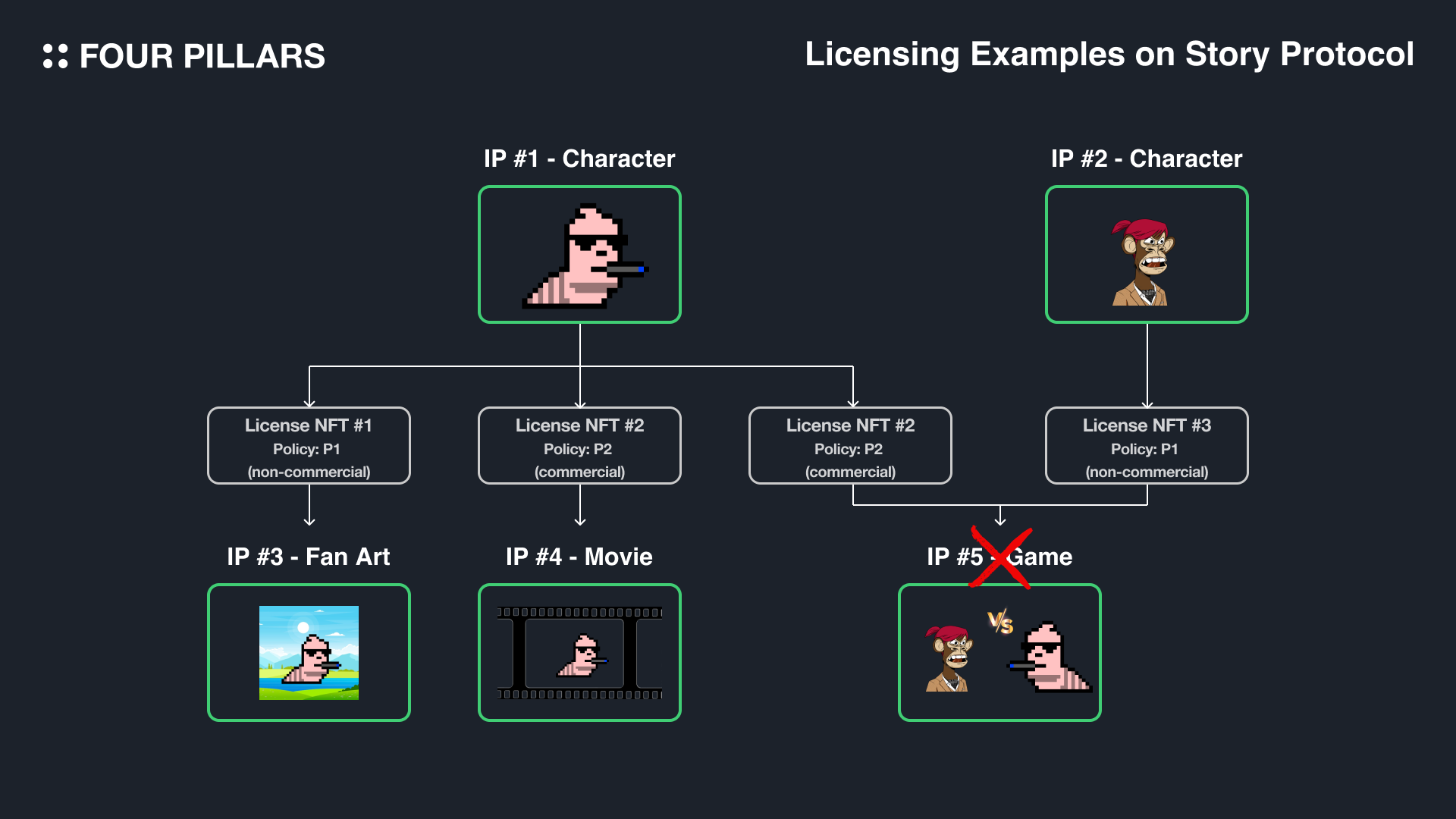

IP rights are represented as License NFTs, containing information like the IPAsset's ID and Policy ID, and identified by a unique License ID. License NFTs follow the ERC-1155 standard, allowing for multiple NFTs. A Policy defines licensing terms related to IP rights, such as commercial use or transferability of licenses. IP owners can choose from a variety of Policies through combinations.

Only the holders of a specific IP's License NFT can create derivative IPs from that parent IP, and upon the registration of the derivative IP under the parent IP, the License NFT gets burned. For instance, let's assume the owner of Larva Lads registered IP #1, minted one License NFT #1 with a non-commercial use policy (P1), and two License NFT #2s with a commercial use policy (P2). The owner of License NFT #1 can burn it to register non-commercial fan art as IP #3. Similarly, the owner of License NFT #2 can register a commercial movie as IP #4.

A derivative IP can also be registered under two parent IPs, allowing for the creation of innovative content through the combination of various IPs. However, if the License NFTs of the two parent IPs have conflicting policies, the derivative IP cannot inherit both. For example, if someone intends to create a commercial game using both Larva Lads and BAYC characters for IP #5, but IP #2's owner issued a License NFT only following the non-commercial P1 policy, registration would be impossible.

4.3.2 Royalty Module

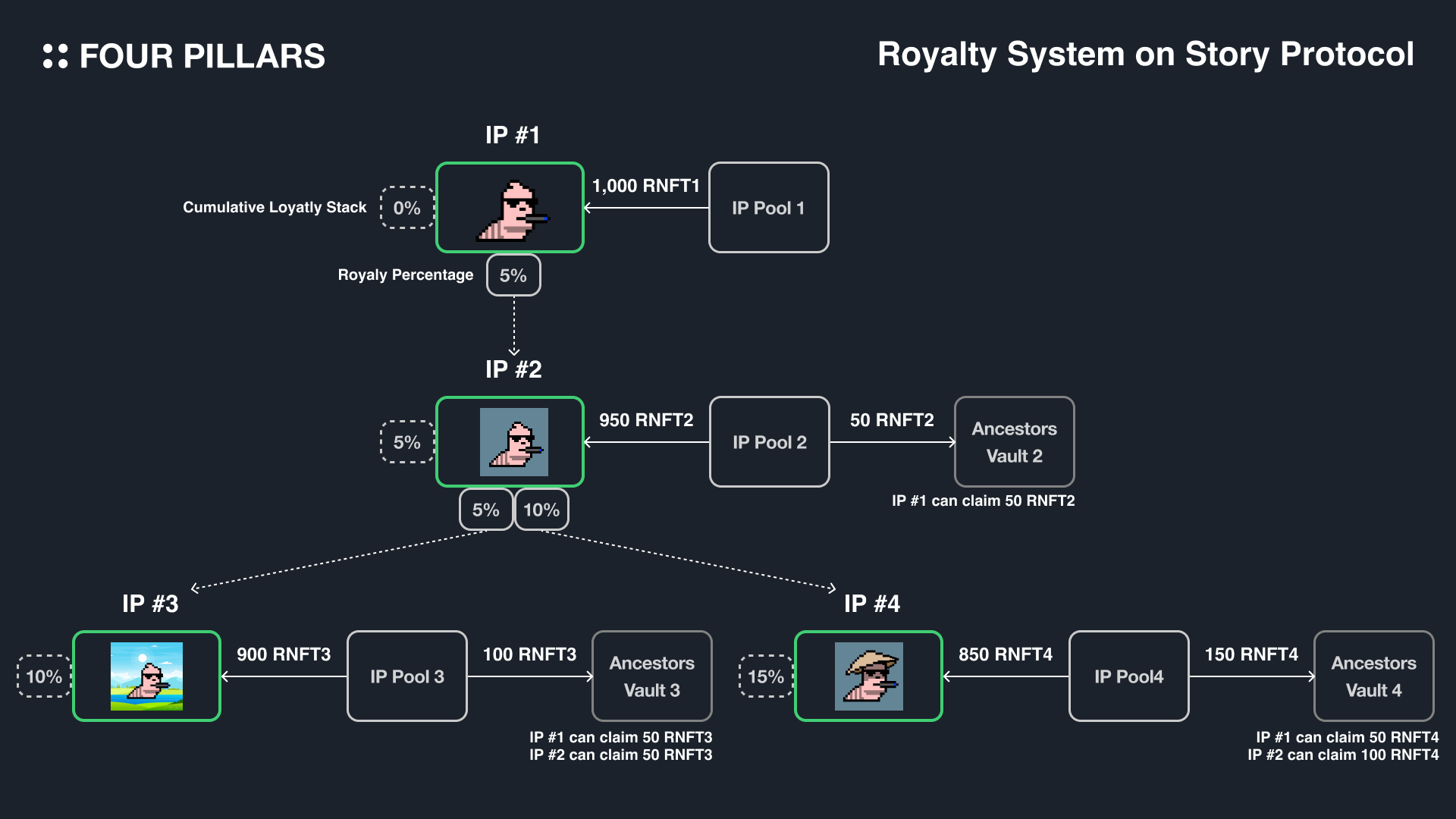

The Story Protocol introduces a feature that enforces royalties for IP usage through code, addressing a common issue in the traditional IP landscape. A Royalty Policy can be defined between two IPAssets, setting the minimum royalty percentage a parent IPAsset can collect from its derivative IPs. Each IPAsset has an IP Pool holding 1,000 ERC-1155 Royalty NFTs, and holders can claim a proportional share of revenue generated from the related IP Pool.

For example, if IP #2 is registered with a 5% royalty to IP #1, then 5% of 1,000 RNFT2 (50 RNFT2) would be deposited in Ancestors Vault 2, and IP #1 would have the right to claim these 50 RNFT2. Similarly, if IP #4 is registered with a 10% royalty to IP #2, then 15% (5% from IP #1 and 10% from IP #2) of 1,000 RNFT4 (150 RNFT4) would be deposited in Ancestors Vault 4, with IP #1 having the right to claim 50 RNFT4 and IP #2 the right to claim 100 RNFT4. This mechanism allows parent IPs to claim a portion of the revenue generated by their derivative IPs.

While tracking IP usage and collecting royalties in the digital realm has been challenging, the Story Protocol successfully addresses this issue. However, as the IP relationship tree deepens, the cumulative royalty percentage might increase significantly, highlighting the importance of selecting appropriate royalty percentages.

4.3.3 Dispute Module

What happens if a malicious user claims to have created an original IP using someone else's IP? To address this, the Story Protocol includes a Dispute Module for mediating disputes. If malicious activity is confirmed, the offending IP and its owner face penalties.

While the IPAccount stores information related to a specific IP, the Registry functions to store the global states of the Story Protocol. The types of Registries include:

IPAsset Registry: Manages the registered IPAssets within the protocol and deploys the corresponding IPAccounts.

Module Registry: Manages and updates the global list of modules and permissionlessly registered hooks.

License Registry: Manages interactions related to License NFTs and stores all information related to licenses.

4.5.1 IP Owners

If IP owners can protect their rights and encourage derivative works by registering their intellectual property as IPAssets (intellectual property contracts) on the Story Protocol, there would be no reason for them not to use it.

4.5.2 Creators

For creators, if their favorite IP is IPAsset'd on the Story Protocol and the benefits of receiving fair royalties offset the hassle or difficulty of using the protocol, there is no reason not to use it.

4.5.3 Investors

If investors want to invest in the royalties of a particular IP, they can easily do so by purchasing Loyalty NFTs through platforms like Opensea or Blur. However, in order for this process to be seamless, first, competitive IPs must be registered on Story Protocol, and second, Story Protocol must be able to effectively manage and track off-chain royalties.

Story Protocol currently lacks the ability to enforce legal action for IP copyright infringement, and tracking royalties off-chain is not straightforward. So, can Story Protocol be the new infrastructure for internet-based IP? I can't say for sure. Nevertheless, the problems that Story Protocol focuses on are real, and they are certainly present across the Internet.

The emergence of technology-based parallel institutions will be an important trend in the future, giving people more choices and stimulating the development of existing infrastructure. Story Protocol is well positioned to play a role as a parallel organization, especially in the IP space. If Story Protocol can identify the clear needs of IP owners and target them sharply, we may soon see an environment where copyright holders do not have to worry about unauthorized use of their creations, and secondary creators can freely recreate the IP they want and demand compensation accordingly.

Thanks to Kate for designing the graphics for this article.

Dive into 'Narratives' that will be important in the next year